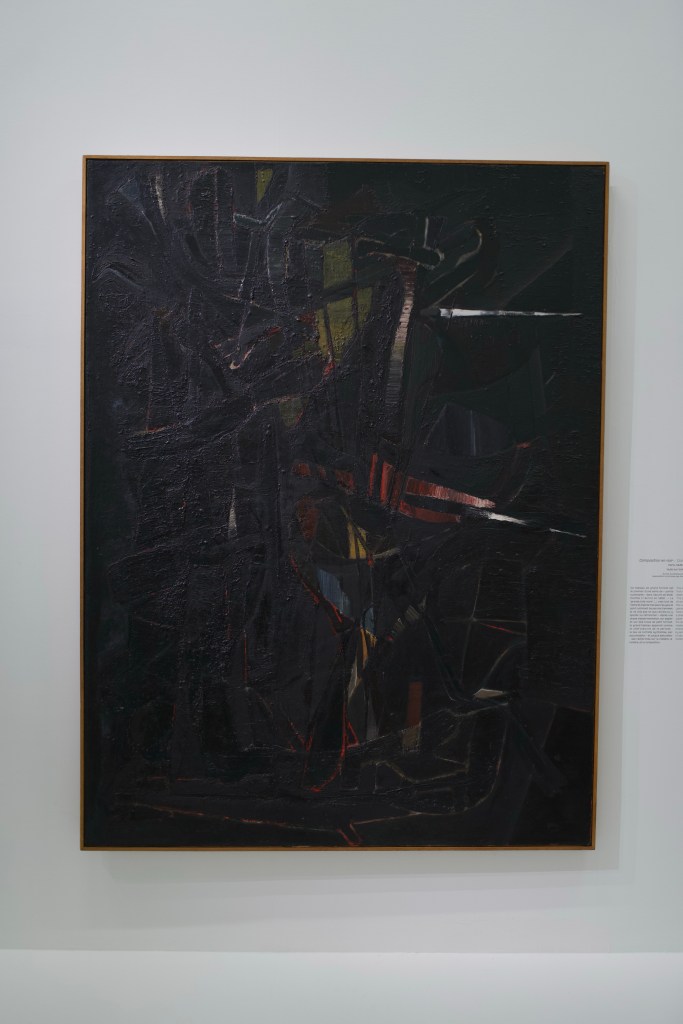

March 26th 1952, Parc des Princes, Paris: for the first night game in the country, the French football team of Robert Jonquet and Jean Baratte lost 0-1 against Sweden. In the stands, Nicolas de Staël (1914-1955) is fascinated by the show of the players in motion under the electric lighting. Back to his workshop and still enthusiastic, he started to paint several works known as ‘Les Footballeurs‘ and ‘Parc des Princes‘.

The largest painting of the ‘Parc des Princes’ series – sold by Christie’s Paris in 2019 for 20 millions of euros – is one of the highlight of the Nicolas de Staël retrospective organized by the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris from September 15th 2023 until January 21st 2024, twenty years after the one presented at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. With 200 works (including 70 drawings) showed in chronological order, the exhibition offered a large overview of de Staël work’s evolution during the fifteen years he painted, featuring some rare and never seen before by the public paitings belonging to 65 private collections and 15 museums.

Travels and first works (1934-1947)

Born in Saint Petersburg in 1914, Nicolas de Staël is three years when the Rusian Revolution broke out and his family had to flee. He soon became orphan and grew up in Belgium. In the mid-thirties, he travelled in the south of France, in Spain, and eventually in Morocco where he met his first wife, Jeannine Guillou. After a year in the Foreign Legion in 1939 as a cartographer, he lived in Nice during three years then moved to Paris. If his first works were portraits mainly inspired by Jeannine (who tragically died after a therapeutic abortion in 1946), he turned to abstraction in 1942, painted dark and sophisticated compositions.

Beyond abstract and figurative painting (1948-1951)

Remaried with Françoise Chapouton, Nicolas de Staël moved to Paris, in a workshop near to the Parc Montsouris. The post war years saw the dispute between the supporters of abstract art and the defenders of a figurative painting. Nevertheless he appeared to be above this debate, stating: “the non figurative trends do not exist […] the painter will always need to have in front of his eyes, from near or far, the source of inspiration in motion which is the sensitive universe.”

Thus, the work of de Staël is marked by a constant questioning and evolution, year after year. The tangle of dark bars of his early abstract paintings became lighter and more colorful (1948), then the shapes broader and more aerated (1949-1950).

From studies on paper until the final version on the canvas, the creation process of de Staël is made of experimentation, amendment and adjustement, as shown by the three works below: the same composition is developed in various color schemes, in smaller format, before achieving the final painting (on the right).

This permanent reasearch in his practice can also be seen through the various formats on which he painted. From small pictures, like this 12,4 x 16,1 cm ‘Oiseau noir’ (a name given by the collector Pierre Granville who bought the work in 1950), to larger format paintings like this 200 x 150 cm ‘Grande composition bleue‘, changing scale allows de Staël to break the routine and try new ideas.

In 1951, he took another direction compared to his works from the previous year: his compositions are now fragmented, turning into mosaics of various colored tessera. Still at the limit between abstract and figurative painting, theses colorful patchworks are becoming flowers.

Depicting the world around (1952-1953)

The following year, in 1952, Nicolas de Staël decided to go out to work. Paris region, Normandy, south of France… he painted more than two hundred forty landscapes, mainly in small and medium formats, inspired either by urban areas or natural sites.

The same year, after attending the football game France – Sweden at the Parc des Princes, he applied the technique he has used in his landscapes to depict his feelings after seeing this sport event. The next month, he wrote to his friend, the poet René Char: “Between sky and earth, on grass that is either red or blue, there whirls a ton of muscle in complete disregard for self […]. What joy! René, what joy!“

Two other large formats realized in 1953, ‘Bouteilles dans l’atelier‘ and ‘L’orchestre‘, show his will to represent in a personal way the colors and the movement of the world around him.

South light (1953-1954)

During the 1953 summer, de Staël went to Provence with his family, before buying an austere and run down house there – le Castelet. During this stay, he fell in love with a young woman, Jeanne Polge, with who he had a passionate and complicated relationship until the end of his life.

Like many artists before him, the sun of the south has illuminated his palette, his paintings becoming brighter. During this period, he also realized a touching portrait of his daughter Anne, that he has had with his late wife Jeannine.

Then, still in 1953, he took all his family (including Jeanne Polge and Ciska Grillet, a friend of René Char) to a trip to Italy, going until Sicilia. There, once again, he has been struck by the light that inspires him a series of painting of Agrigente and Syracuse landscapes and ruins, painted afterwards in his workshop in Provence.

Purple, yellow, orange and red: de Staël used a strong palette to express his feelings, like on this ‘Agrigente’ view below in which he kept only a few lines of perspective converging to a colored impasto in the centre of the canvas.

Last works, Antibes (1954-1955)

In 1954, alternating short trips between the south of France and his workshop in Paris, de Staël is still in search of new sensations. The works of this period are smoother and sleeker, as he simplifies his compositions.

In september 1954, he moved to Antibes to stay closer to Jeanne Polge. Experimenting new techniques, he uses cotton and gauze pads to spread the color, creating an ethereal feel like in ‘Coin d’atelier fond bleu’ or ‘Les mouettes’. His last works also include still-lifes, reinterprating this genre with his own language.

On March 16th 1955, he jumped out of the terrace of his house at Antibes, letting several unachieved works. In a letter addressed to his dealer, he wrote: “I don’t have the strength to finish my paintings.” He was forty.

The exhibition proposed a rich and comprehensive journey through the evolution of Nicolas de Staël work, showing the different steps of the painter-researcher who had always stayed beyond the debate about abstract and figurative art. The show also brings further insights by telling the personal life of the painter. Eventually, the visit ends with this awesome and poetic ‘Les mouettes’ (‘The seagulls‘), far from the idea that one usually has of de Staël.

Sources:

- Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris website

- Le Monde, article published on September 14th 2023

- ‘Parc des Princes (Les grands footballeurs)’, Christie’s sale on October 17th 2019

Photos credits: @elegantinparis