In the mid-19th century, the Realist movement in France marked a break with academic art and its representation of an idealized beauty frozen in the past. Painters such as Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) sought to depict the everyday life of their time, the working class and rural people.

Bilal Hamdad (born in Algeria in 1987) studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Bourges and later in Paris, graduating in 2018. Taking photos during his strolls and errands, he began painting the streets and people of Paris, working from a shared studio in the northern suburbs. In 2023–2024, he was an artist-in-residence at the Casa de Velázquez—an artistic French institution located in Madrid, Spain. He is now represented by Galerie Templon.

From October 17, 2024, until February 8, 2025, the exhibition Paname at the Petit Palais shows around twenty of Hamdad’s paintings made between 2019 and 2024, hung among the museum’s permanent collection. Through his portraits and his street scenes set in cafés or the subway, the exhibition establishes a dialogue between the 2020s and the late 19th to early 20th centuries, echoing the Realist paintings belonging to the Paris museum.

Portraits from life

The visit starts with L’Angélus, a nod to Jean-François Millet’s painting, in which a peasant couple bow in a field to say a prayer, the Angelus. In this modern interpretation, a young man, Birane — whose portrait is displayed further in another room — is sitting on a stair railing in a subway station, in the same meditative posture as Millet’s figures. Furthermore, just behind his subject, Hamdad has painted the same village in the distance, outlined similary.

All along the exhibition, the portraits of the artist’s friends and acquaintances seem to engage in a dialogue with their counterparts painted more than an hundred years earlier. For instance, Olivia — a young girl dressed in a simple black dress and vivid red sandals, who looks up with a boyish air — stands next to several portrayals of 19th-century bourgeois women.

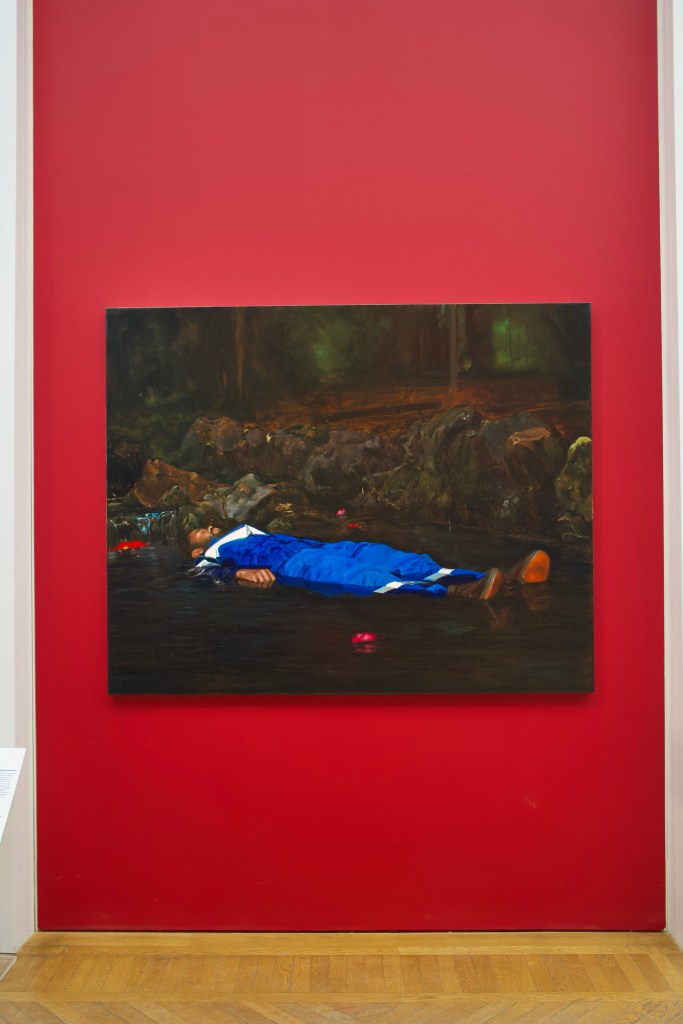

With Nuit égarée and L’Horizon, Hamdad offers a more fantastical approach: inspired by Ophelia, the painting by the English artist John Everett Millais, the reclining bodies with closed eyes, floating on stagnant waters, evoke recumbent statues in a peaceful yet eerie atmosphere. The strong contrast created by the bright colors of the figures’ clothes and the dark background reinforces this impression.

In the métropolitain

The Parisian subway — métro in French — is a recurring motif in Hamdad’s work. In Rivoli and Le Mirage, solitary figures, looking pensive or lost in thought, wander through empty corridors and platforms. The composition is even more intriguing in L’Attente, with its vanishing point in the upper left corner of the canvas: is this man or woman coming out of the subway – up to the light – or waiting for someone they have seen upstairs, as suggested by the title?

Outside the métro, the contrast is striking with the lonely people encountered underground: a colorful and multicultural crowd symbolizes today’s Paris. Rive Droite is likely one the most emblematic work of the show: at the exit of the popular Barbès-Rochechouart station, in northern Paris, a street vendor selling grilled corn catches the eye, drawing it toward the center of the painting — where two young black men are passing by. Behind them, a white couple is strolling hand in hand, along with a man walking his dog. In the background, at the top of the stairs, the artist has hidden a reference to the model posing in L’Atelier, a painting by Gustave Courbet.

Paname, a large-format painting, could be the centerpiece of the exhibition that bears its name. Along with Rive Droite, this canvas is exhibited in one of the main galleries of the Petit Palais, right next to the emblematic Les Halles, painted by Léon Lhermitte in 1895. Both works present a similar composition: a dense, vibrant throng — at Les Halles’ food market yesterday, and at an improvised market just outside the métro today. As previously, a young girl in a pink dress draws attention to the center of the painting, along with the nearby figures — a black mother with a stroller, a woman leaning on the railing, and an older black man holding a red bag.

A drink at the café

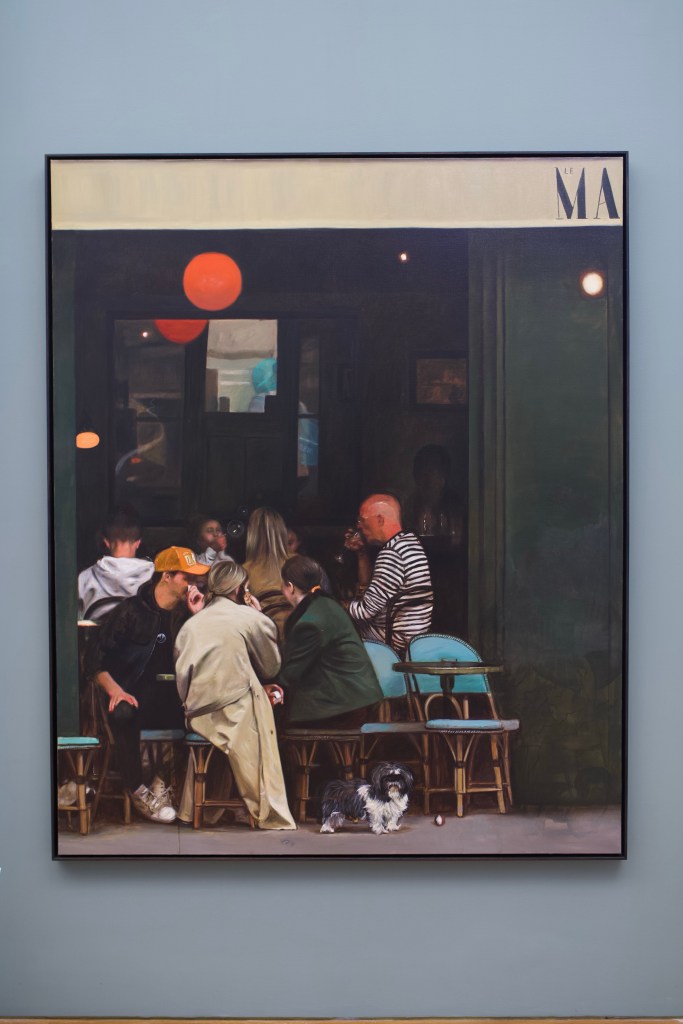

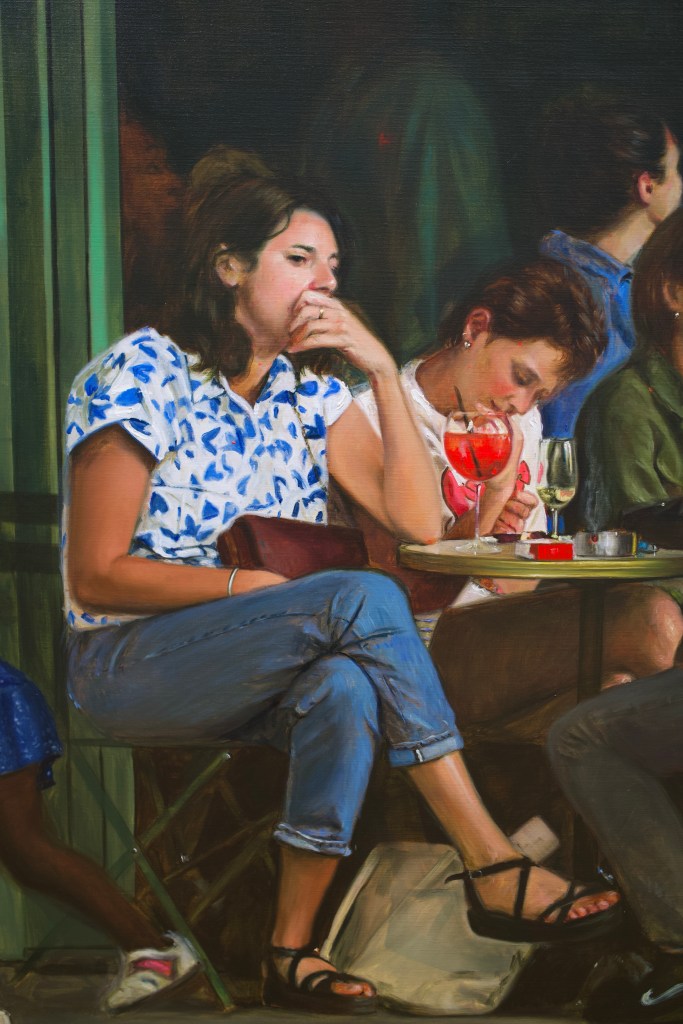

After wandering in the subway, let’s have a coffee or a spritz on a terrace on Rue de la Roquette! Typical of the Parisian lifestyle, Hamdad captures these moments spent in cafés with friends or family. The addition of small details—a woman scrolling on her smartphone, a Perrier bottle, or a pair of sneakers—adds a realistic touch and situates the scenes firmly in the 2020s.

As highlighted earlier, Hamdad often adds small bursts of bright color—an orange cap here, a red jacket there—to catch the viewer’s eye and energize the composition, in the manner of Francisco de Goya with his touches of red. In these modern street scenes, he continues to pay homage to past masters—the orange globe in Reflets evokes Monet’s sunsets, while the paintings in the background of Lueurs d’un soir recall Velázquez’s Las Meninas.

One last fun detail: in many of these group scenes (see also Rive Droite and Paname above), a dog appears—sometimes looking directly at the viewer, as if reversing the gaze. This impression of life as theatre is further reinforced by the curtains in Lueurs d’un soir II and Immersion nocturne.

Final thoughts

Afterwards, I realized that none of the subway scenes actually show a train. Instead, Hamdad focuses on stations with distinctive designs—Arts et Métiers, with its copper cladding, or Louvre–Rivoli, with its antique statues, for instance. Like the cafés, the métro stands as a strong symbol of Parisian identity over the years, beyond the clichés—and ‘Paname’ is undoubtedly the main character of the exhibition. Meanwhile, the display amid the Petit Palais collection sheds new light on his paintings and establishes him as a contemporary realist, with several nods to the masters of the past. In doing so, he offers a snapshot of today’s Paris—multicultural and popular.

Further readings:

- Billa Hamdad’s website

- Artist’s profile on Galerie Templon’s website

- ‘Paname‘ exhibition on the Petit Palais’s website

Photos credits: @elegantinparis