During the first half of the 2010s, I remember the final years of the Louvre des Antiquaires, wedged between the Palais-Royal and the Louvre Museum: as I walked through the narrow, dimly lit corridors, only a few antique shops remained in the huge building—the last survivors of galleries that once housed around 250 stores. Opened in 1978, the site succeeded the Grands Magasins du Louvre, a department store founded during the Second Empire. Initially a gallery of luxury stores on the ground floor of the Grand Hôtel du Louvre, which had occupied the building since its opening in 1855, it expanded to the entire edifice twenty years later and became a fashionable department store, alongside the Bon Marché on the other bank of the Seine.

It is in this building steeped in history that the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain unveiled its new premises in October 2025, following five years of renovation. With the Exposition générale show that marked its opening, the private institution glances back at its past, celebrating more than forty years of contemporary art since its creation in 1984.

An open-plan museum

Designed by star architect Jean Nouvel—who also conceived the Fondation’s former home on Boulevard Raspail—the layout’s greatest achievement lies in offering multiple perspectives on the collections, displayed across three floors and within open, flowing spaces. As a result, works installed on the lower floor such as Panama, Spitzbergen, Nova Zemblaya by Belgian artist Panamarenko—a true submarine whose name evokes three symbolic, far-flung destinations and serves as an invitation to travel—are first glimpsed from above at the beginning of the visit, before being encountered up close at the end with its true 22 horsepower diesel engine.

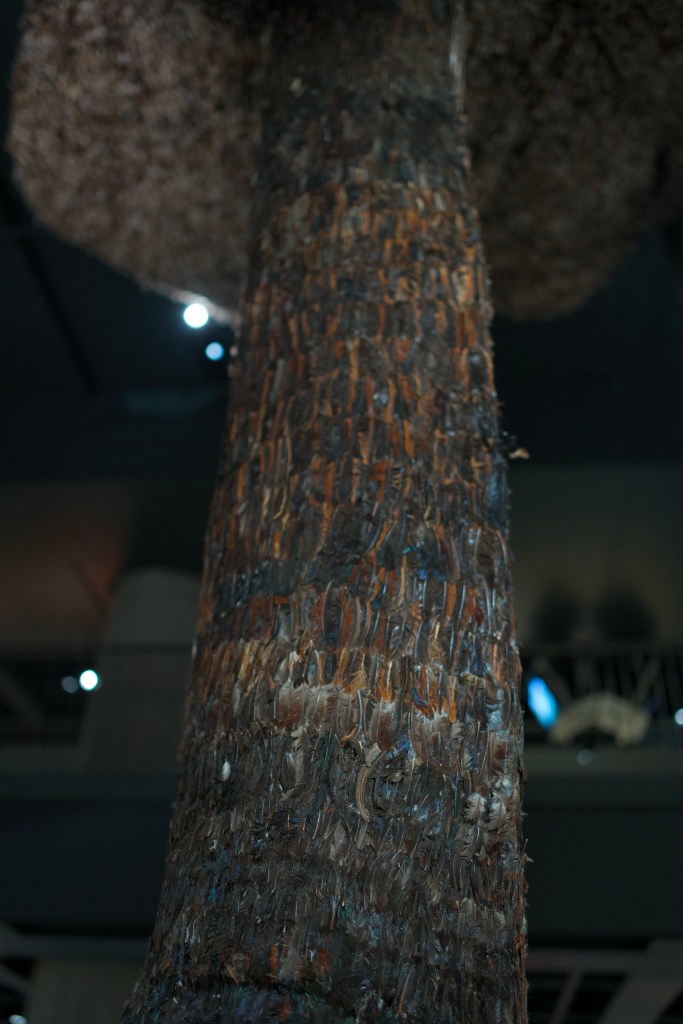

Similarly, Miracéus by Brazilian artist Solange Pessoa—a large-scale installation representing a giant tree covered with thousands of bird feathers, echoing voodoo or shamanic rituals—appears differently depending on whether it is viewed from below, above, or at eye level, and reemerges, sometimes partially, as visitors move through the museum.

A throwback to the Fondation’s history

After his first exhibition at the Fondation in 2006, Japanese artist Tadanori Yokoo began, in 2014, a series of portraits of artists and personalities linked to the institution, named The Inhabitants. Completed in 2024, the series ultimately grew to more than 140 paintings. Car manufacturer Enzo Ferrari – for the groundbreaking exhibition of the Scuderria in 1987, Alain Dominique Perrin – founder of the institution in the 1980s, and the French sculptor César – who presented the monumental installation, Hommage à Eiffel, during the first years of the Fondation, are for instance represented in this curated who’s who.

Founded in 1984 in Jouy-en-Josas, near Paris, before relocating to the capital in 1994, the French jewellery and watchmaking house Cartier paved the way for private patronage by international luxury groups such as LVMH (Fondation Louis Vuitton) and Kering (Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection) in France. By acquiring works by artists from different horizons and regularly organizing exhibitions and events, the institution helped introduce them to a wider audience. Several works presented in Exposition générale echo past exhibitions, from Gérard Garouste’s Les Indiennes (1988) and Jean-Michel Othoniel’s Crystal Palace (2003) to, more recently, Damien Hirst’s Cerisiers en fleurs (2021), all nodding to the Fondation’s history.

Various media, various ways of expression

From Christian Bontanski’s Éphémères installation – combining video projections of hundreds of mayflies, one-day-lifespan flying insects, drifting across white veils – to Raymond Depardon’s photographs of the French countryside from his Rural series, the Fondation Cartier collection spans a wide range of media in contemporary art.

Architecture also features in the exhibition, which opens with a selection of utopian scale models, including works by Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez, who developed a political and futuristic—yet poetic—vision of Kinshasa. As the visit continues, Israeli artist Absalon’s Propositions d’habitations emerges as a hybrid work at the intersection of architecture, design, and sculpture.

Project for Third-Millennium Kinshasa, 1997

Since the late 1990s, Freddy Mamani has developed a neo-Andean architectural style rooted in the culture of the Aymara, an Indigenous people of the Bolivian Altiplano. For the exhibition, he recreated one of his salones de eventos, colorful and flamboyant, within the Fondation’s new building.

In 1994, Huang Yong Ping’s solo show Devons-nous encore construire une grande cathédrale ? questioned the meaning of the written memory, and the freedom of knowledge and expression through printed media-books and newspapers. The exhibition referred to the artistic project Wir bauen eine Kathedrale (‘We Are Building a Cathedral’), initiated by Joseph Beuys in the 1980s, with three fellow artists-Anselm Kiefer, Janis Kounellis and Enzo Cucchi-in which the so-called cathedral serves as a metaphor for the collective construction of knowledge and society. In Yong Ping’s work, the four artists’ ideas are embodied in their writings, which are pulped and placed on some stools and a table, with a photograph of their meeting in the background.

Having renewed sculpture since the mid-1990s, Ron Mueck is represented in the exhibition by one of his ultra-realistic figures, Woman with Shopping. Inspired by a scene from everyday life, the Australian artist quickly sketched a woman he had seen in the street. Lost in thought, she holds two orange shopping bags and carries a small infant against her chest, tucked beneath her coat. As a result, the sculpture, slightly smaller than life-size, is both touching and unsettling.

With Tracing Fallen Sky, American artist Sarah Sze presents a work that defies classification, combining a pendulum, video projections, and a wide range of media. The installation consists of 116 3D-printed stainless-steel elements, along with their imprints, arranged in a large circle of marble dust, evoking an archaeological ruin. Across this surface, videos of materials in transformation are projected, blurring the boundary between the virtual and the physical.

A global vision of contemporary art

If you look at the origins of the artists I’ve mentioned so far, you will notice they come from all five continents. One of the strengths of the Fondation’s collection is that it offers a perspective on art from the last four decades that is not centered on the Western world.

Both from Brazil, Eliane Duarte and Véio draw on the culture and techniques of their country. Duarte does so through a composition made of side-by-side balls of coloured yarn (Ribalta), which echoes the ancestral sewing practices of Brazilian women, while Véio’s Grupo de Penitentes depicts a religious procession taking place during penitential rituals in his region.

Another perspective on Brazilian culture is offered by Luiz Zerbini, whose Natureza Espiritual da Realidade brings together vegetal elements and a range of objects collected during his travels—shells, stones, tree trunks, and fishing gear—arranged on herbarium tables as contemporary still lifes.

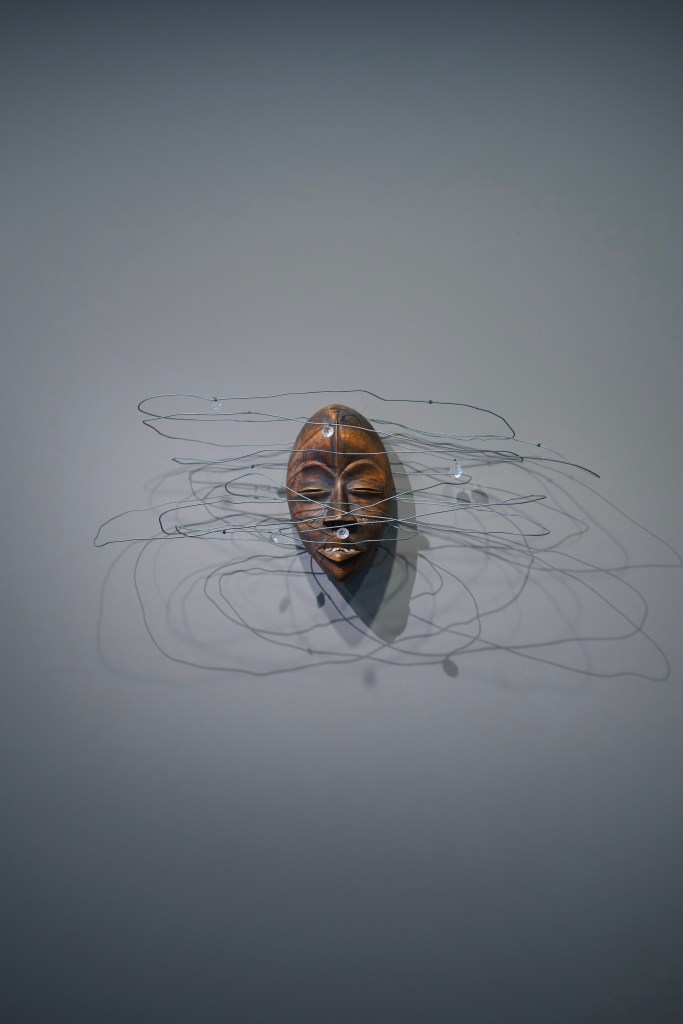

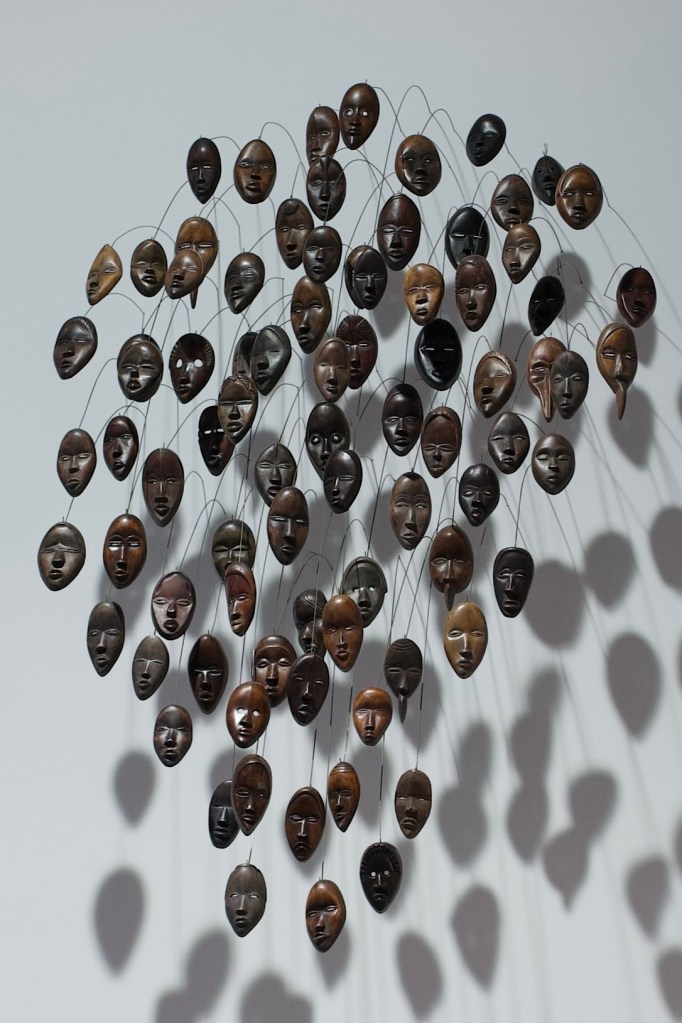

Active since the 1970s, American artist David Hammons is a key figure of the Black Arts Movement, which helped bring African American art into the cultural mainstream. His works in the Fondation’s collection cast a critical light on the fetishization and exoticization of African art. In The Mask, a Dan mask from Côte d’Ivoire appears trapped in a web of metallic wire, while in Untitled (1997) the artist stacks some twenty African masks, bound with wire and capped with a mirror—recalling those found on nkisi nkondi figures. In another Untitled work from 1995, he assembled eighty-four Dan ‘passport’ masks, echoing Arman’s work Accumulation d’âmes, presented in the exhibition Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, held at MoMA in 1984.

Malick Sidibé, nicknamed the “Eye of Bamako” was a Malian photographer who captured the spirit of Bamako’s youth at a pivotal moment in the 1960s, as the country gained independence from French colonial rule. His shots of young men and women dancing, hanging out, and partying bear witness to their encounter with Western culture.

with Her Tinted Glasses, 1969 ; A young gentleman 1978

The Man Posing as a Musician Behind his Car, 1971 ; Friends Night, 1964

At first glance, Double Eclipse by Argentine artist Guillermo Kuitca appears to depict a cityscape at night. On closer inspection, however, the buildings reveal themselves to be stacks of chairs and beds, unfolding a dreamlike yet eerie vision that hovers between fantasy and reality.

Located in the basement and visible from the ground-floor alleyways, the monumental Muro en rojos (7 meters high and 8 meters wide), composed of rectangular woven elements and colored in a gradient from red to light green, with a range of orange hues in between, evokes Olga de Amaral’s landscapes as well as the brick façades of her native Bogotá.

Nearby, Virgil Ortiz’s ceramics are made from red clay sourced from Cochiti Pueblo, a village in New Mexico that is home to Native American Pueblo communities. His works reinterpret traditional Pueblo satirical figurines, infusing them with contemporary references drawn from science fiction and punk culture.

One of the most striking works in the show is perhaps the installation NIGHT WOULD NOT BE NIGHT WITHOUT THE CRICKET. Created in collaboration with Soundwalk Collective, it invites visitors to walk through a dark corridor, experiencing eight soundscapes drawn from Bernie Krause’s archive, who has recorded nearly 5,000 hours of field bioacoustics since 1968. The result is a singular visual, auditory, and sensory experience.

Final thoughts

Jouy-en-Josas is a lovely town about 18 kilometers from Paris, surrounded by nature in the bucolic Vallée de la Bièvre. It hosts the Domaine du Montcel, where the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain was first established in 1984. Nowadays, the estate is a luxury hotel, Dolce by Wyndham Versailles, where I had a drink last summer. In the park still stand César’s monumental installation Hommage à Eiffel, along with Arman’s Long Term Parking, reminiscent of the site’s artistic past.

Being born in the early 1980s, I was amused to realize that the Fondation’s collection features a curated selection of contemporary art created during my lifetime. Drawing on this heritage, the new building is expected to help the Fondation continue promoting contemporary art, with an approach different from that of its two ‘competitors’-the Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Bourse de Commerce–Pinault Collection.

Photos credits: @elegantinparis